Promise and Performance: The Trials and Trails of India’s Industrialization

The 1960s and early 1970s in India are vital for understanding patterns of growth and structural tendencies of the national economy at large because in many ways they mark certain fundamental transitions that were, in fact, already observable by then. Agricultural growth rate fell sharply form 3.64 percent in the 50s to a mere 1.68 percent in the 60s and ‘non-foodgrain output growth was uniformly lower than foodgrain growth’. (Mohan Rao 1997: 7) Similarly, despite a fourfold increase in industrial production between 1950-1975, it can be seen that the average level of industrial production fell from 7.7 percent between 1951-65 to a sluggish 3.6 percent per annum during the decade 1965-75. (Nayyar, 1978) - Table 1. There was also a general slowdown in the heavy industry, with growth in metal production falling from a healthy 12.5 per cent per annum in the first period to a mere 2.5 per cent per annum in the second. (McCartney, 2009) Further, there have also been studies which pointed out the increased emergence of unutilized manufacturing capacity and a concomitant decline in the rate of industrial growth, as already noted. (KN Raj, 1976) Therefore, it is illuminating to see what this clear conjecture of declining growth rates in both industry and agriculture during the 60s imply in regards to the sustainability of the economic models of growth and productivity implemented primarily through the influential Second Plan.

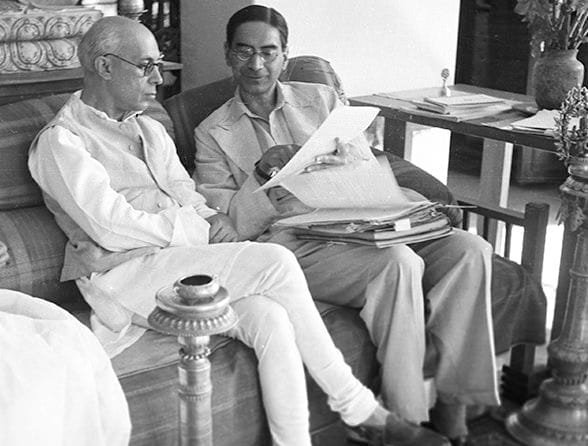

Nehru and Mahalanobis (Source)

In this essay, I argue that, although there had been exogenous factors such as poor harvests and loss of foreign demand and aid leading to foreign exchange shortages, the failure of the Mahalanobis strategy as evidenced by the economic slump from the mid-sixties, among other things, was caused by a much more fundamental failure at the heart of the strategy — namely, the incorrigible insistence on capital goods industrialization as being the primary means of national development within an overall context of income maldistribution, and demand deficiency. As India focused on real capital formation as the panacea for problems of employment and growth, the promise of perpetuation and sustainability of this model has been belied by the subsequent crises. In this context, I believe it is inevitable and imperative that one ask what it was that churned the “passions” of policy-makers and politicians to undertake heavy industrialization as the singular pathway to a certain ideal state of living. This is not to deny the diversification of economic structure, establishing of higher irrigation facilities and increased but inequitable potentials of self-sufficiency that this stress of large-scale manufacturing was able to accomplish, but it is to excavate and investigate the underlying ideologies, insecurities, inhibitions and formative powers that structured, sustained and directed the state-machinery and resource-allocative forces to take up this cause. In this essay, however, due to lack of space, I will focus only on aspects of economic promise and performance, nevertheless acknowledging the centrality of the historical question.

Table 1. (Nayyar, 1978)

Firstly, the interrelations between consumer goods, capital goods for producing capital goods, and capital goods for producing consumer goods was seen to be central to evaluating and achieving effective economic growth, as articulated in the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. (Chakravarty, 1987) The concomitant necessity here was also a need to increase the production of consumer goods using labour-intensive methods, (as opposed to direct capital investment by the government) and a general increase in employment in order to have the consumer demand proportionately expanding. Along with this, the overall success of the plan was also dependent on the inter-sectoral harmony. Any slowdown or insufficient performance in the agricultural sector would also lead to a dampening of the industrial growth. This would be the case if (i) agricultural supplies were limited because in India’s traditional industries such as that of jute, cotton, and sugar, were heavily dependent on agriculture for their raw material; (ii) if the ‘surplus of wage goods and investible resources are not forthcoming’, (Nayyar 1978: 5) then this could lead to slackening of output and inflationary situations, and finally, (iii) a general demand for the industrial goods will fall with rising food costs, severely hindering non-foodgrain consumption expenditure.

It should be noted here that the sources for financing and sustaining the conditions necessary for long-term productive growth was dependent as much on general public investment and the subsequent diversification of capital goods into manufactured goods, as it was on the ability of the government to procure resources for reinvestment by either taxing or incentivizing or directing the growing incomes of private players. The latter is important — for both social and political reasons as well - because a concentrated increase in the consumption of non-essentials and luxury goods at the cost of public investment and inequitable distribution of national income can only lead to an economy that is both unstable and unsustainable. Thus, it was assumed that the government would be able to socialize current income flows by financing investments through savings construed by private entities within an overall context of increased productivity of the public sector and community-held agricultural sector. Therefore, even if certain patterns of public investment can play an important role in Indian agriculture, as Chakravarty (1979) notes, ‘on demand side far more significant effects can be obtained in the long run sense by changes in agrarian relations.’ As a case for illustrating the inequitable demand, we can look at the year 1964-65, where it has been calculated that, in the rural sector, ‘the richest 10 per cent of the population was responsible for 32.2 per cent of the total consumption of industrial goods, whereas the poorest 50 per cent accounted for only 22 per cent of the total. Consumption inequalities were even more pronounced in the urban sector, where the top decile purchased 39.3 per cent of the industrial goods and the bottom five deciles absorbed just'19.9 per cent of the total.’ (Nayyar 1978: 7)

Here, it is pertinent to raise insights from Bagchi (1970) who identifies two critical problems with the strategy; namely, (i) ensuring balanced increase of supplies of different types of goods, and (ii) the inevitable discrepancies that arise between the distribution of demand and planned supplies of consumer goods. While the former may lead to loss of demand for capital goods if ‘capital-goods industries outpaces the planned rate of increase in the output of consumer-goods industries’, the latter can potentially exacerbate the problems of ‘inflation and evolution of the black market both in socialist and mixed economies’. At the core of his analysis is the plausible idea that the limited controlling powers and socio-political inhibitions of mixed economy governments cannot ensure cogency and cooperation with the more dominant economic forces, namely, the expenditure patterns of private sector. Therefore, it is important for us to acknowledge the presence of rural oligarchy in determining the course, feasibility and effectiveness of industrial growth (Mitra, 1977) because (i) it must be pointed out that export-led foreign-capital induced industrial growth cannot be sustainable as far as the domestic consumer demand is low due to unequal income distribution. This is because export-led policies will require alliances between ruling coalitions and urban industrial elite which, often, will have to come at the expense of the rural based rich peasantry. (ii) Consequently, a resolution to turn to external markets to replace the domestic demand bottleneck would entail policies that will ease licensing measures for industries and incentivizing MNCs (multinational corporations), cutting back on indirect taxes on luxury goods (because the majority demand is from urban and rural elite who indulge in such consumption), or cutting the level of income tax levied on the rich in order improve their scope for consumption and savings and so on — all of which would entail severe redirecting of resources and incentives for the welfare of the elite as opposed to more plausibly rural-poor-friendly policies such as fertilizer subsidies, public investment in irrigation and so on.

Given that, the social and political nature of elite demands should also be noted. They had to be concerned about protecting the structural benefits accruable by rigid maintenance of hierarchized divisions of land holdings, proprietary relations, tenurial conditions and caste privilege dynamics. One could claim that, in a supply constrained system, an increased role of public investment led growth could cure the demand deficiencies. But, as Chaudhuri (1998) notes, ‘even when public investment rises, what is crucial is the structure and character of investment’. If public investment is primarily utilised in accordance with political intents of decision-makers and the elite, then the issues will only be exacerbated.

Although, Nehruvian agrarian policies in the Second Plan did theoretically focus on achieving political power to the rural poor peasants while also improving agricultural productivity using labour-intensive methods, none of these ideals were substantiated or realized. Varshney (1998) insightfully shows how intra-Congress party struggles and discrepant realities on the ground, coupled with the increasingly failing overall agrarian productivity and loss of foreign exchange led to the eventual collapse of the institutional strategy employed by the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. One must note here that, along with the lack of local political support and mileage that was required to mobilize the resources for enabling the policy measures, the strategy made an oversight in at least two ways. Firstly, as Chakravarty (1987) notes, they treated the agrarian sector as a ‘bargain sector’ wherein it was optimistically believed that a slight capital investment and organizational restructuring through co-operatives, panchayats and indirect measures such as rural education would help increase the ever-required food supplies, thus balancing inter-sectoral costs, and cutting import costs. Thus, the government was confident enough to halve the total outlay in investment in agriculture and irrigation in the Second Plan, along with an absolute decline in irrigation expenditures.

But, more importantly, the assumption that industrial growth from well-achieving capital goods sector would rise in tandem with agrarian surplus proved to be a far cry. This was especially untenable given that there was no considerable plan delineating financial distributional mechanisms that must be at play in order to ensure equitable income distribution, even if there was, presumably, a formidable agrarian surplus. In other words, for equitable growth and increased productivity, there has to be implementational strategies concerning not only inter-sectoral relations, (questions dealing with price incentives, surplus labour, technocratic adjustments, movement of raw materials etc.) but also those of intra-agrarian forces (sub-regional variabilities, natural resource differentials, proprietary and holding relations, centre-state relations etc.) must be actively acknowledged. We see that in the Second Plan, the latter was meant to be achieved mostly through social restructuring and political programming as opposed to heavy economic investments. This proved futile in an overall scenario of a mixed economy and intra-party fractions where the government did not simply have the muscle to wrest its policy measures into fruition.

Consequently, it should be mentioned, thereby, that one of the main limitations of the Mahalanobis strategy was that it did not prioritize the ‘income distribution’ problem as it was centred on the issue of industrial productivity. This was so to such an extent that even the growth of consumption was schematized and imagined as being dependent on ‘prior increase in the capacity of the capital goods sector’. (Chakravarty 1987: 28) Thus, it is provocatively and profoundly insightful when Chakravarty compares this model as being a peculiar form of ‘trickle-down’ strategy because ‘it promised an improvement in the consumption level only as the end product of a process of accumulation’, even though it did not favour any high-income group as being necessary for accumulation. However, I think this opens up avenues to consider the three periods of planning as being a form of state-capitalism, as opposed to being strictly socialist. Additionally, it is pertinent we engage with this question about the nature of the state as well, because, as delineated by Byres (1997), theorising the nature of the post-colonial state as being either ‘instrumental/Hegelian’, ‘interventionist’, or ‘multi-class’ and so on has implications on how we approach planning, and in determining our priorities and possible blind-spots.

References:

Bagchi, Amiya. (1970) ‘Long-Term Constraints on India’s Industrial Growth, 1951-1968’ in Robinson, E.A.G. and Kidron, Michael (eds.) Economic Development in South Asia, London: McMillan and Co Ltd. pp. 170-193

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1979) ‘On the Question of Home Market and Prospects of Indian Growth’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 14, No. 30/32. pp 1229-1242

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1987) Development Planning: The Indian Experience, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Mohan Rao, J. (1997) ‘Agricultural Development under State Planning’ in Byres, J. Terence (ed.) The State, Development Planning and Liberalisation in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 127-172

McCartney, Matthew. (2009) India- the Political Economy of Growth, Stagnation and the State, 1951- 2007, London: Routledge

Nayyar, Deepak. (1978) ‘Industrial Development in India: Some Reflections on Growth and Stagnation’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 13, No. 31/33. pp. 1265-1278

Raj, KN. (1976) ‘Growth and Stagnation in Indian Industrial Development’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 11, No. 5/7. pp. 223-236

Varshney, Ashutosh. (1998) Democracy, Development and the Countryside: Urban-Rural Struggles in India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

The Gradual Origins of Indo-Lanka Liberalization Reforms

When dealing with the question of structural reforms in South Asia, there are two interesting issues that arise, especially in the case of India and Sri Lanka. Firstly, we notice that the impact that the reforms have had in India were quite negligible in improving the rates of growth in manufacturing industry, total factor productivity rates, aggregate economic growth, employment rates in the manufacturing sector and of capital formation. Many scholars argue that in fact a much larger shift in the trend of growth rates can be observed during the 80s in India, that is, a decade before the reforms were carried out most forcefully. Conversely, in Sri Lanka, post-1977 reforms led to a burst of short-term economic growth with a jump in GDP rates within four to five years. Secondly, we see that in the case of both Sri Lanka and India, this new economic vision of reforms was as much a product of immediate and internal economic crises as it was a political project to redefine new alliances and state priorities.

Dr. Manmohan Singh, then Finance Minister of India, officially announcing the liberalization reforms in 1991. (Source)

In this essay, I argue that there are, broadly, two factors can be identified that explain the gradual structural transformation of these economies: (i) firstly, the growing dissatisfaction with the state-led planning economy, which which has arisen not only because of the states’ underperformance over the decades, but also because of a general ideological shift in understanding the role and the nature of the state; (ii) secondly, the gradual culmination of internal crises, coincidentally with various exogenous shocks or externally dependent or determining conditionalities. It is also worth noting here that, additionally and perhaps more interestingly — and this is to some extent a partial product of the two factors mentioned above — a peculiar link started to be drawn between socio-ethnic conflicts and the advancement of a liberalized economy, which became an essential part of the discourse of nationalism and sovereignty in general. In other words, the third factor underscores the attempts of these states to produce ‘economistic’ discourses in order to either make sense of or justify concomitant incidences of ethnic violence seen at the time.

Given this, there were generally two camps of thought which actively debated these issues. One, largely critical of the reforms, emphasized that the supposed failures of state-led development were not as acute as neoliberal writers were claiming, and that therefore, it was important to trace the political economy changes, i.e.; the role of bureaucratic-businessmen alliances, or the shifting governmental priorities pushed forth by, and in favour of, elite interests in order to understand the emergence of reforms. Then there were those who actively advocated reforms, pointing out to the stifling measures of state-led planning economy, which was unable to unleash the entrepreneurial spirits of the nation, or improve the overall economic efficiency, and therefore could not integrate into the global market by attracting foreign capital and increasing incentives for domestic private investment. There are, needless to say, considerable variations within each of these camps which I will try to present as well.

The underlying argument here is that a failure of the socialist developmental schemes led to a gradual but partial reversal in the states’ responses to the constraints present at the time of reforms which motivated them to liberalize. Here, I use the word ‘partial’ in a double sense: in lieu of Corbridge (2000), as being partial or favourable to elite interests, and secondly, as ‘incomplete’, in the sense that there was never a complete or absolute withdrawal of the state from the economic apparatus.

Two Models of Divergence

There is an interesting divergence in the development models of India and Sri Lanka before they took on the reforms, which evinces that diversity in approaches to state intervention exists even within development states. While India predominantly focused on heavy industrialization and capital formation as a way to alleviate poverty, by contrast Sri Lanka prioritized public spending on social welfare mechanisms and various subsidizing policies. Over the long-run, while failure to (i) mobilize domestic resources, (ii) direct and sustain savings into productive investment, (iii) to create rural demand and increase agrarian productivity, and (iv) persistent levels of poverty, unemployment and under capacity utilization etc. led to an economic slump in India in the 70s, in the case of Sri Lanka, we see that an overdependence on plantation-led exports revenue could not sustain the pervasive expansion of the public sector in regulation, production and welfare which eventually led to a deteriorating exchange position. (Herring, 1987)

In a sense, these long-term experiences with state-led development that either underperformed (as was the case in 70s India) or pushed the economy to the brink (Sri Lanka in mid-70s) could be seen as feasible economic explanations that led the states’ gradual embrace to a more market-led liberalization economy. In India, a visible shift toward furtherliberalization was already discernible in the 80s before it achieved a state of ‘reforms proper’ in the early 90s. Gandhi’s regime, which returned to power in the 1980 elections banking on the socialist rhetoric of ‘garibi hatao’, could already be seen to be making policies in favour of the indigenous businessmen and industrialists. Also, these tendencies were relatively heightened in the succeeding Rajiv Gandhi regime. A spate of industry deregularization policies were introduced along with the lifting of trade restrictions. In the early 80s, ‘thirty-two groups of industries were delicensed without any investment limit, and this was followed by removal of licensing requirements for all industries except for those on a small negative list, subject to investment and location limitations.’ (Ghosh, 1998) Similarly, in 1985, the coming of Open General License increased the list of exportable items and exporters were now able to access imported inputs at world prices. However, it should be noted that these changes were occurring alongside an increased cutting of subsidies in the public distribution system and dissolution of the Food for Work program in 1982. (Kohli, 2006) Thus, we observe here not only the commencing of these explicit liberalization- friendly policies, but an active emergence of a renewed economic propensity favouring newer priorities. As Kohli (2006) notes, the state was now increasingly seeing itself as a mediator in coalition with big businessmen to achieve economic growth as opposed to the earlier idea of planning economy. Thus, these lucid remarks by Ghosh captures the changing dynamics of the 80s economy:

While the economic expansion that occurred was dominated by the straightforward Keynesian stimulus of large government deficits, the role of planned investments in this process was very limited. Indeed, it was government expenditure that led to economic expansion which was finally reflected in an expenditure-led import-dependent middle class consumption boom. The effective irrelevance of planning meant that growth patterns were determined much more by market processes than by state direction. (Ghosh, 1998, pp. 321)

However, there are, in my view, some certain qualifications that have to be made here. Although, state direction did decrease, as Ghosh points out, this is not to say that India, even in the early 90s, was able to, or willing to, totally ‘withdraw from the economy’, whatever that may entail. Instead, we see that, as in the case of Sri Lanka, undertaking an economic logic of liberalization essentially means a shifting of governmental priorities and a fundamental reshaping of the nature of the state, rather than, what Herring calls, ‘wholesale privatization campaign’. (Herring, 1987)

The Partiality of Reforms

While in India the gradual tilting was discernible through various policies employed in the 80s, in Sri Lanka this shift was most pronounced in the 1971 austerity budget. But, as in the case of India, the role of the state was not completely minimized but only changed. Now, the states would play a lesser role in regulation, commerce, and production. These were discernible by an increased change in composition of overall investment with private investment crossing the levels of public investment in both states and the many deregulation procedures undertaken. However, the state had still to play an active role in developing public infrastructure, which was thought to create the initial conditions necessary to attract and sustain private investment. One subtle irony here was that while the reformist philosophy and the pro-business economy, in practice, emphasized banking on already established private actors, the theoretical rhetoric was that the capital would actually flow into capital-scarce areas and improve labour-intensive growth, thus fuelling employment. But the problem with this was twofold. Firstly, these expectations did not actually materialize as can be construed by the largely unchanging industrial growth rates and employment rates. Secondly, it paved the way for eliminating the existing structures of welfare provisioning mechanisms. Thus, instead of strengthening these measures, which had been instrumental in sustaining formidable rates of human development in these countries, governments took an anti-labour and anti-poor turn.

It should be noted here that these changeshave taken place within an overall context of partiality. Thus, for example, the passing of Essential Public Service Act in 1979 in Sri Lanka gave the state the powers to outlaw trade union activities across the states. Likewise, the Tamil rural poor had to face unfavourable conditions as, for instance, when the imports of agricultural commodities such as grapes, chilis and onions were liberalized in Jaffna, while the paddy and potato crops, which were mostly grown by the Sinhalese farmers, were protected. Even the public investment programs, which were largely funded by external monetary agencies and banks such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, as well as through foreign aid, have led to discriminatory projects. The Mahaweli Development Project was, for instance, seen as a matter of nationalist pride, while the Tamils were protesting against it because the project was deemed to encroach lands that traditionally belonged to them. (Dunham and Jayasuriya, 2001) Similarly, the insistence of the pro-reform Jayawardane government in 1977 on reducing food subsidies was also not a product of economic rationalizing. There was no established evidence or justification to suggest that the closed economy’s trade policies or stunted growth rates was a direct result of public expenditure on food subsidies. (Herring, 1987) In fact, as Dunham and Jayasuriya (2001) pointed out, the annual subsidies on Air Lanka was exceeding domestic expenditure on public transport and sometimes also on food subsidies. Here we can note that the reforms were driven not only by economic considerations, but also by broader socio-ethnic and ideological leanings.

Sri Lanka 1977 riots, the year of liberalization reforms. Source

Just as in Sri Lanka, we can observe a similar bias in Indian reforms. However, it should be noted here that these reforms were not singularly beneficial to the elite classes and favoured majoritarian ethnicities. It is true that there was a short-term growth that was made possible following the 1977 reforms in Sri Lanka and, furthermore, the government was able to deal effectively with the fiscal deficit crisis after the reforms. However, the question of the sustainability and bias of these reforms has to be acknowledged. Thus, the continued failure of the Indian state to invest in education and health infrastructure contributes to the violent inequalities in enabling access to accruing social capital for the lower classes and depressed castes. Additionally, the determining importance of possessing certain initial conditions that favour economic growth (such as availability of infrastructure, presence of formidable human capital, durable climate for investment etc.) stands out in the way post-reform growth pans out. Atul Kohli (2006) discusses this very issue while analysing divergent growth trends in Indian states. Likewise, I believe that it can be assumed that this is true for national economies as well. A further proof of this could be a greater success that East Asian countries have been able to achieve, unlike, for example, India. The fact that South Korea and Taiwan in particular had well-established infrastructure and large state power played a role in ensuring high growth rates through open, export-oriented economies. In contrast, in India, fragmented power structures and differing demands of varied interest-groups have led to slower efforts to rapidly integrate into the global economy. Thus, we can see that the presence of favourable ‘initial conditions’ and a pro-business state are equally important in determining the implementation of these policies.

Thus, one of the cruel ironies was that these programmes of economic stabilization could not necessarily lead to political stabilization, moreover, they led to just the opposite result - increased political instability.

References Cited:

Dunham, David and Jayasuriya, Sirisa. (2001) ‘Liberalisation and Political Decay: Sri Lanka’s Journey from a Welfare State to a Brutalised Economy’. Netherlands: Institute of Social Studies.

Ghosh, Jayati. (1998) ‘Liberalization Debates’ in Terrence J. Byers (ed.) The Indian Economy: Major Debates Since Independence , Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 295-335.

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1980s’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 13. pp. 1251-1259

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1990s and Beyond’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 14. pp. 1361-1370

Corbridge, Stuart and Harriss, John. (2000) Reinventing India: Liberalization, Hindu Nationalism and Popular Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press

Herring, Ronald. (1987) ‘Economic Liberalisation Policies in Sri Lanka: International Pressures, Constraints and Supports’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 22, No. 8, pp. 325-333