Promise and Performance: The Trials and Trails of India’s Industrialization

The 1960s and early 1970s in India are vital for understanding patterns of growth and structural tendencies of the national economy at large because in many ways they mark certain fundamental transitions that were, in fact, already observable by then. Agricultural growth rate fell sharply form 3.64 percent in the 50s to a mere 1.68 percent in the 60s and ‘non-foodgrain output growth was uniformly lower than foodgrain growth’. (Mohan Rao 1997: 7) Similarly, despite a fourfold increase in industrial production between 1950-1975, it can be seen that the average level of industrial production fell from 7.7 percent between 1951-65 to a sluggish 3.6 percent per annum during the decade 1965-75. (Nayyar, 1978) - Table 1. There was also a general slowdown in the heavy industry, with growth in metal production falling from a healthy 12.5 per cent per annum in the first period to a mere 2.5 per cent per annum in the second. (McCartney, 2009) Further, there have also been studies which pointed out the increased emergence of unutilized manufacturing capacity and a concomitant decline in the rate of industrial growth, as already noted. (KN Raj, 1976) Therefore, it is illuminating to see what this clear conjecture of declining growth rates in both industry and agriculture during the 60s imply in regards to the sustainability of the economic models of growth and productivity implemented primarily through the influential Second Plan.

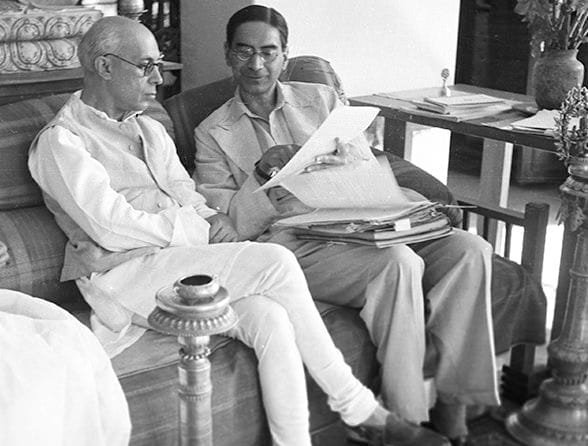

Nehru and Mahalanobis (Source)

In this essay, I argue that, although there had been exogenous factors such as poor harvests and loss of foreign demand and aid leading to foreign exchange shortages, the failure of the Mahalanobis strategy as evidenced by the economic slump from the mid-sixties, among other things, was caused by a much more fundamental failure at the heart of the strategy — namely, the incorrigible insistence on capital goods industrialization as being the primary means of national development within an overall context of income maldistribution, and demand deficiency. As India focused on real capital formation as the panacea for problems of employment and growth, the promise of perpetuation and sustainability of this model has been belied by the subsequent crises. In this context, I believe it is inevitable and imperative that one ask what it was that churned the “passions” of policy-makers and politicians to undertake heavy industrialization as the singular pathway to a certain ideal state of living. This is not to deny the diversification of economic structure, establishing of higher irrigation facilities and increased but inequitable potentials of self-sufficiency that this stress of large-scale manufacturing was able to accomplish, but it is to excavate and investigate the underlying ideologies, insecurities, inhibitions and formative powers that structured, sustained and directed the state-machinery and resource-allocative forces to take up this cause. In this essay, however, due to lack of space, I will focus only on aspects of economic promise and performance, nevertheless acknowledging the centrality of the historical question.

Table 1. (Nayyar, 1978)

Firstly, the interrelations between consumer goods, capital goods for producing capital goods, and capital goods for producing consumer goods was seen to be central to evaluating and achieving effective economic growth, as articulated in the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. (Chakravarty, 1987) The concomitant necessity here was also a need to increase the production of consumer goods using labour-intensive methods, (as opposed to direct capital investment by the government) and a general increase in employment in order to have the consumer demand proportionately expanding. Along with this, the overall success of the plan was also dependent on the inter-sectoral harmony. Any slowdown or insufficient performance in the agricultural sector would also lead to a dampening of the industrial growth. This would be the case if (i) agricultural supplies were limited because in India’s traditional industries such as that of jute, cotton, and sugar, were heavily dependent on agriculture for their raw material; (ii) if the ‘surplus of wage goods and investible resources are not forthcoming’, (Nayyar 1978: 5) then this could lead to slackening of output and inflationary situations, and finally, (iii) a general demand for the industrial goods will fall with rising food costs, severely hindering non-foodgrain consumption expenditure.

It should be noted here that the sources for financing and sustaining the conditions necessary for long-term productive growth was dependent as much on general public investment and the subsequent diversification of capital goods into manufactured goods, as it was on the ability of the government to procure resources for reinvestment by either taxing or incentivizing or directing the growing incomes of private players. The latter is important — for both social and political reasons as well - because a concentrated increase in the consumption of non-essentials and luxury goods at the cost of public investment and inequitable distribution of national income can only lead to an economy that is both unstable and unsustainable. Thus, it was assumed that the government would be able to socialize current income flows by financing investments through savings construed by private entities within an overall context of increased productivity of the public sector and community-held agricultural sector. Therefore, even if certain patterns of public investment can play an important role in Indian agriculture, as Chakravarty (1979) notes, ‘on demand side far more significant effects can be obtained in the long run sense by changes in agrarian relations.’ As a case for illustrating the inequitable demand, we can look at the year 1964-65, where it has been calculated that, in the rural sector, ‘the richest 10 per cent of the population was responsible for 32.2 per cent of the total consumption of industrial goods, whereas the poorest 50 per cent accounted for only 22 per cent of the total. Consumption inequalities were even more pronounced in the urban sector, where the top decile purchased 39.3 per cent of the industrial goods and the bottom five deciles absorbed just'19.9 per cent of the total.’ (Nayyar 1978: 7)

Here, it is pertinent to raise insights from Bagchi (1970) who identifies two critical problems with the strategy; namely, (i) ensuring balanced increase of supplies of different types of goods, and (ii) the inevitable discrepancies that arise between the distribution of demand and planned supplies of consumer goods. While the former may lead to loss of demand for capital goods if ‘capital-goods industries outpaces the planned rate of increase in the output of consumer-goods industries’, the latter can potentially exacerbate the problems of ‘inflation and evolution of the black market both in socialist and mixed economies’. At the core of his analysis is the plausible idea that the limited controlling powers and socio-political inhibitions of mixed economy governments cannot ensure cogency and cooperation with the more dominant economic forces, namely, the expenditure patterns of private sector. Therefore, it is important for us to acknowledge the presence of rural oligarchy in determining the course, feasibility and effectiveness of industrial growth (Mitra, 1977) because (i) it must be pointed out that export-led foreign-capital induced industrial growth cannot be sustainable as far as the domestic consumer demand is low due to unequal income distribution. This is because export-led policies will require alliances between ruling coalitions and urban industrial elite which, often, will have to come at the expense of the rural based rich peasantry. (ii) Consequently, a resolution to turn to external markets to replace the domestic demand bottleneck would entail policies that will ease licensing measures for industries and incentivizing MNCs (multinational corporations), cutting back on indirect taxes on luxury goods (because the majority demand is from urban and rural elite who indulge in such consumption), or cutting the level of income tax levied on the rich in order improve their scope for consumption and savings and so on — all of which would entail severe redirecting of resources and incentives for the welfare of the elite as opposed to more plausibly rural-poor-friendly policies such as fertilizer subsidies, public investment in irrigation and so on.

Given that, the social and political nature of elite demands should also be noted. They had to be concerned about protecting the structural benefits accruable by rigid maintenance of hierarchized divisions of land holdings, proprietary relations, tenurial conditions and caste privilege dynamics. One could claim that, in a supply constrained system, an increased role of public investment led growth could cure the demand deficiencies. But, as Chaudhuri (1998) notes, ‘even when public investment rises, what is crucial is the structure and character of investment’. If public investment is primarily utilised in accordance with political intents of decision-makers and the elite, then the issues will only be exacerbated.

Although, Nehruvian agrarian policies in the Second Plan did theoretically focus on achieving political power to the rural poor peasants while also improving agricultural productivity using labour-intensive methods, none of these ideals were substantiated or realized. Varshney (1998) insightfully shows how intra-Congress party struggles and discrepant realities on the ground, coupled with the increasingly failing overall agrarian productivity and loss of foreign exchange led to the eventual collapse of the institutional strategy employed by the Nehru-Mahalanobis strategy. One must note here that, along with the lack of local political support and mileage that was required to mobilize the resources for enabling the policy measures, the strategy made an oversight in at least two ways. Firstly, as Chakravarty (1987) notes, they treated the agrarian sector as a ‘bargain sector’ wherein it was optimistically believed that a slight capital investment and organizational restructuring through co-operatives, panchayats and indirect measures such as rural education would help increase the ever-required food supplies, thus balancing inter-sectoral costs, and cutting import costs. Thus, the government was confident enough to halve the total outlay in investment in agriculture and irrigation in the Second Plan, along with an absolute decline in irrigation expenditures.

But, more importantly, the assumption that industrial growth from well-achieving capital goods sector would rise in tandem with agrarian surplus proved to be a far cry. This was especially untenable given that there was no considerable plan delineating financial distributional mechanisms that must be at play in order to ensure equitable income distribution, even if there was, presumably, a formidable agrarian surplus. In other words, for equitable growth and increased productivity, there has to be implementational strategies concerning not only inter-sectoral relations, (questions dealing with price incentives, surplus labour, technocratic adjustments, movement of raw materials etc.) but also those of intra-agrarian forces (sub-regional variabilities, natural resource differentials, proprietary and holding relations, centre-state relations etc.) must be actively acknowledged. We see that in the Second Plan, the latter was meant to be achieved mostly through social restructuring and political programming as opposed to heavy economic investments. This proved futile in an overall scenario of a mixed economy and intra-party fractions where the government did not simply have the muscle to wrest its policy measures into fruition.

Consequently, it should be mentioned, thereby, that one of the main limitations of the Mahalanobis strategy was that it did not prioritize the ‘income distribution’ problem as it was centred on the issue of industrial productivity. This was so to such an extent that even the growth of consumption was schematized and imagined as being dependent on ‘prior increase in the capacity of the capital goods sector’. (Chakravarty 1987: 28) Thus, it is provocatively and profoundly insightful when Chakravarty compares this model as being a peculiar form of ‘trickle-down’ strategy because ‘it promised an improvement in the consumption level only as the end product of a process of accumulation’, even though it did not favour any high-income group as being necessary for accumulation. However, I think this opens up avenues to consider the three periods of planning as being a form of state-capitalism, as opposed to being strictly socialist. Additionally, it is pertinent we engage with this question about the nature of the state as well, because, as delineated by Byres (1997), theorising the nature of the post-colonial state as being either ‘instrumental/Hegelian’, ‘interventionist’, or ‘multi-class’ and so on has implications on how we approach planning, and in determining our priorities and possible blind-spots.

References:

Bagchi, Amiya. (1970) ‘Long-Term Constraints on India’s Industrial Growth, 1951-1968’ in Robinson, E.A.G. and Kidron, Michael (eds.) Economic Development in South Asia, London: McMillan and Co Ltd. pp. 170-193

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1979) ‘On the Question of Home Market and Prospects of Indian Growth’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 14, No. 30/32. pp 1229-1242

Chakravarty, Sukhamoy. (1987) Development Planning: The Indian Experience, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Mohan Rao, J. (1997) ‘Agricultural Development under State Planning’ in Byres, J. Terence (ed.) The State, Development Planning and Liberalisation in India, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 127-172

McCartney, Matthew. (2009) India- the Political Economy of Growth, Stagnation and the State, 1951- 2007, London: Routledge

Nayyar, Deepak. (1978) ‘Industrial Development in India: Some Reflections on Growth and Stagnation’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 13, No. 31/33. pp. 1265-1278

Raj, KN. (1976) ‘Growth and Stagnation in Indian Industrial Development’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 11, No. 5/7. pp. 223-236

Varshney, Ashutosh. (1998) Democracy, Development and the Countryside: Urban-Rural Struggles in India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

The Gradual Origins of Indo-Lanka Liberalization Reforms

When dealing with the question of structural reforms in South Asia, there are two interesting issues that arise, especially in the case of India and Sri Lanka. Firstly, we notice that the impact that the reforms have had in India were quite negligible in improving the rates of growth in manufacturing industry, total factor productivity rates, aggregate economic growth, employment rates in the manufacturing sector and of capital formation. Many scholars argue that in fact a much larger shift in the trend of growth rates can be observed during the 80s in India, that is, a decade before the reforms were carried out most forcefully. Conversely, in Sri Lanka, post-1977 reforms led to a burst of short-term economic growth with a jump in GDP rates within four to five years. Secondly, we see that in the case of both Sri Lanka and India, this new economic vision of reforms was as much a product of immediate and internal economic crises as it was a political project to redefine new alliances and state priorities.

Dr. Manmohan Singh, then Finance Minister of India, officially announcing the liberalization reforms in 1991. (Source)

In this essay, I argue that there are, broadly, two factors can be identified that explain the gradual structural transformation of these economies: (i) firstly, the growing dissatisfaction with the state-led planning economy, which which has arisen not only because of the states’ underperformance over the decades, but also because of a general ideological shift in understanding the role and the nature of the state; (ii) secondly, the gradual culmination of internal crises, coincidentally with various exogenous shocks or externally dependent or determining conditionalities. It is also worth noting here that, additionally and perhaps more interestingly — and this is to some extent a partial product of the two factors mentioned above — a peculiar link started to be drawn between socio-ethnic conflicts and the advancement of a liberalized economy, which became an essential part of the discourse of nationalism and sovereignty in general. In other words, the third factor underscores the attempts of these states to produce ‘economistic’ discourses in order to either make sense of or justify concomitant incidences of ethnic violence seen at the time.

Given this, there were generally two camps of thought which actively debated these issues. One, largely critical of the reforms, emphasized that the supposed failures of state-led development were not as acute as neoliberal writers were claiming, and that therefore, it was important to trace the political economy changes, i.e.; the role of bureaucratic-businessmen alliances, or the shifting governmental priorities pushed forth by, and in favour of, elite interests in order to understand the emergence of reforms. Then there were those who actively advocated reforms, pointing out to the stifling measures of state-led planning economy, which was unable to unleash the entrepreneurial spirits of the nation, or improve the overall economic efficiency, and therefore could not integrate into the global market by attracting foreign capital and increasing incentives for domestic private investment. There are, needless to say, considerable variations within each of these camps which I will try to present as well.

The underlying argument here is that a failure of the socialist developmental schemes led to a gradual but partial reversal in the states’ responses to the constraints present at the time of reforms which motivated them to liberalize. Here, I use the word ‘partial’ in a double sense: in lieu of Corbridge (2000), as being partial or favourable to elite interests, and secondly, as ‘incomplete’, in the sense that there was never a complete or absolute withdrawal of the state from the economic apparatus.

Two Models of Divergence

There is an interesting divergence in the development models of India and Sri Lanka before they took on the reforms, which evinces that diversity in approaches to state intervention exists even within development states. While India predominantly focused on heavy industrialization and capital formation as a way to alleviate poverty, by contrast Sri Lanka prioritized public spending on social welfare mechanisms and various subsidizing policies. Over the long-run, while failure to (i) mobilize domestic resources, (ii) direct and sustain savings into productive investment, (iii) to create rural demand and increase agrarian productivity, and (iv) persistent levels of poverty, unemployment and under capacity utilization etc. led to an economic slump in India in the 70s, in the case of Sri Lanka, we see that an overdependence on plantation-led exports revenue could not sustain the pervasive expansion of the public sector in regulation, production and welfare which eventually led to a deteriorating exchange position. (Herring, 1987)

In a sense, these long-term experiences with state-led development that either underperformed (as was the case in 70s India) or pushed the economy to the brink (Sri Lanka in mid-70s) could be seen as feasible economic explanations that led the states’ gradual embrace to a more market-led liberalization economy. In India, a visible shift toward furtherliberalization was already discernible in the 80s before it achieved a state of ‘reforms proper’ in the early 90s. Gandhi’s regime, which returned to power in the 1980 elections banking on the socialist rhetoric of ‘garibi hatao’, could already be seen to be making policies in favour of the indigenous businessmen and industrialists. Also, these tendencies were relatively heightened in the succeeding Rajiv Gandhi regime. A spate of industry deregularization policies were introduced along with the lifting of trade restrictions. In the early 80s, ‘thirty-two groups of industries were delicensed without any investment limit, and this was followed by removal of licensing requirements for all industries except for those on a small negative list, subject to investment and location limitations.’ (Ghosh, 1998) Similarly, in 1985, the coming of Open General License increased the list of exportable items and exporters were now able to access imported inputs at world prices. However, it should be noted that these changes were occurring alongside an increased cutting of subsidies in the public distribution system and dissolution of the Food for Work program in 1982. (Kohli, 2006) Thus, we observe here not only the commencing of these explicit liberalization- friendly policies, but an active emergence of a renewed economic propensity favouring newer priorities. As Kohli (2006) notes, the state was now increasingly seeing itself as a mediator in coalition with big businessmen to achieve economic growth as opposed to the earlier idea of planning economy. Thus, these lucid remarks by Ghosh captures the changing dynamics of the 80s economy:

While the economic expansion that occurred was dominated by the straightforward Keynesian stimulus of large government deficits, the role of planned investments in this process was very limited. Indeed, it was government expenditure that led to economic expansion which was finally reflected in an expenditure-led import-dependent middle class consumption boom. The effective irrelevance of planning meant that growth patterns were determined much more by market processes than by state direction. (Ghosh, 1998, pp. 321)

However, there are, in my view, some certain qualifications that have to be made here. Although, state direction did decrease, as Ghosh points out, this is not to say that India, even in the early 90s, was able to, or willing to, totally ‘withdraw from the economy’, whatever that may entail. Instead, we see that, as in the case of Sri Lanka, undertaking an economic logic of liberalization essentially means a shifting of governmental priorities and a fundamental reshaping of the nature of the state, rather than, what Herring calls, ‘wholesale privatization campaign’. (Herring, 1987)

The Partiality of Reforms

While in India the gradual tilting was discernible through various policies employed in the 80s, in Sri Lanka this shift was most pronounced in the 1971 austerity budget. But, as in the case of India, the role of the state was not completely minimized but only changed. Now, the states would play a lesser role in regulation, commerce, and production. These were discernible by an increased change in composition of overall investment with private investment crossing the levels of public investment in both states and the many deregulation procedures undertaken. However, the state had still to play an active role in developing public infrastructure, which was thought to create the initial conditions necessary to attract and sustain private investment. One subtle irony here was that while the reformist philosophy and the pro-business economy, in practice, emphasized banking on already established private actors, the theoretical rhetoric was that the capital would actually flow into capital-scarce areas and improve labour-intensive growth, thus fuelling employment. But the problem with this was twofold. Firstly, these expectations did not actually materialize as can be construed by the largely unchanging industrial growth rates and employment rates. Secondly, it paved the way for eliminating the existing structures of welfare provisioning mechanisms. Thus, instead of strengthening these measures, which had been instrumental in sustaining formidable rates of human development in these countries, governments took an anti-labour and anti-poor turn.

It should be noted here that these changeshave taken place within an overall context of partiality. Thus, for example, the passing of Essential Public Service Act in 1979 in Sri Lanka gave the state the powers to outlaw trade union activities across the states. Likewise, the Tamil rural poor had to face unfavourable conditions as, for instance, when the imports of agricultural commodities such as grapes, chilis and onions were liberalized in Jaffna, while the paddy and potato crops, which were mostly grown by the Sinhalese farmers, were protected. Even the public investment programs, which were largely funded by external monetary agencies and banks such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, as well as through foreign aid, have led to discriminatory projects. The Mahaweli Development Project was, for instance, seen as a matter of nationalist pride, while the Tamils were protesting against it because the project was deemed to encroach lands that traditionally belonged to them. (Dunham and Jayasuriya, 2001) Similarly, the insistence of the pro-reform Jayawardane government in 1977 on reducing food subsidies was also not a product of economic rationalizing. There was no established evidence or justification to suggest that the closed economy’s trade policies or stunted growth rates was a direct result of public expenditure on food subsidies. (Herring, 1987) In fact, as Dunham and Jayasuriya (2001) pointed out, the annual subsidies on Air Lanka was exceeding domestic expenditure on public transport and sometimes also on food subsidies. Here we can note that the reforms were driven not only by economic considerations, but also by broader socio-ethnic and ideological leanings.

Sri Lanka 1977 riots, the year of liberalization reforms. Source

Just as in Sri Lanka, we can observe a similar bias in Indian reforms. However, it should be noted here that these reforms were not singularly beneficial to the elite classes and favoured majoritarian ethnicities. It is true that there was a short-term growth that was made possible following the 1977 reforms in Sri Lanka and, furthermore, the government was able to deal effectively with the fiscal deficit crisis after the reforms. However, the question of the sustainability and bias of these reforms has to be acknowledged. Thus, the continued failure of the Indian state to invest in education and health infrastructure contributes to the violent inequalities in enabling access to accruing social capital for the lower classes and depressed castes. Additionally, the determining importance of possessing certain initial conditions that favour economic growth (such as availability of infrastructure, presence of formidable human capital, durable climate for investment etc.) stands out in the way post-reform growth pans out. Atul Kohli (2006) discusses this very issue while analysing divergent growth trends in Indian states. Likewise, I believe that it can be assumed that this is true for national economies as well. A further proof of this could be a greater success that East Asian countries have been able to achieve, unlike, for example, India. The fact that South Korea and Taiwan in particular had well-established infrastructure and large state power played a role in ensuring high growth rates through open, export-oriented economies. In contrast, in India, fragmented power structures and differing demands of varied interest-groups have led to slower efforts to rapidly integrate into the global economy. Thus, we can see that the presence of favourable ‘initial conditions’ and a pro-business state are equally important in determining the implementation of these policies.

Thus, one of the cruel ironies was that these programmes of economic stabilization could not necessarily lead to political stabilization, moreover, they led to just the opposite result - increased political instability.

References Cited:

Dunham, David and Jayasuriya, Sirisa. (2001) ‘Liberalisation and Political Decay: Sri Lanka’s Journey from a Welfare State to a Brutalised Economy’. Netherlands: Institute of Social Studies.

Ghosh, Jayati. (1998) ‘Liberalization Debates’ in Terrence J. Byers (ed.) The Indian Economy: Major Debates Since Independence , Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 295-335.

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1980s’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 13. pp. 1251-1259

Kohli, Atul. (2006) ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India, 1980-2005: Part 1: The 1990s and Beyond’ , Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 14. pp. 1361-1370

Corbridge, Stuart and Harriss, John. (2000) Reinventing India: Liberalization, Hindu Nationalism and Popular Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press

Herring, Ronald. (1987) ‘Economic Liberalisation Policies in Sri Lanka: International Pressures, Constraints and Supports’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 22, No. 8, pp. 325-333

COVID-19 Undermines Peru’s Economic Stability

In Perú, we’ve been in confinement for more than a month and don’t know exactly when the lockdown will be lifted. The state of emergency was declared (article 137.1 of Peruvian Constitution) and the restriction of some of our rights and liberties (like freedom of displacement, association or the right to work) is accepted because we need to deal with the virus, and everyone seems to be handling the situation well, inclined to a desire to resume our rights, lives and maintain our well-being. Families are staying home in order to avoid being infected with COVID-19, which is characterized by its ability to contaminate rapidly. For this reason, the government has put in practice some measures in order to guarantee people’s basic needs. Most breadwinners can’t go to work, students can’t go to schools. It seems that now we are living in a different era, in which our digital devices are our only contact with the outside. In this article, we’re going to make a recount of the measures the Peruvian government has been putting in action in order to mitigate the economic crisis that can result from the outbreak of this extremely dangerous virus.

So far, more than 45.000 victims of coronavirus have been reported and the cases increase day after day. Being at home, at the same time, helps people avoid being in contact with others and, hence, reinforces our plan of steering clear of the virus. These measures, however, involve some important economic cost. The decisions taken by each country reflect what they value more, in some cases, it can be human life and, in others, economy. Trump’s administration is being criticized because of this and he defends himself arguing that: “We cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself.” However, both decisions promise positive and negative consequences, and the latter need to be mitigated.

Some economic sectors are still working like food industry, which can’t be paralyzed and is guaranteed to operate during this difficult time. Health professionals that work with coronavirus patients will be paid an extra 3.000 soles (885 USD) for their hazardous work on this recent time. On the other hand, tourism, commerce and other important economy sectors, considered non-essential, remain paralyzed. For this reason, Perú has put in practice the plan “Reactiva Perú”, which aims to keep our economy moving and implements other measures to protect people’s primary rights. It is noteworthy, at this point, that Perú is qualified as the best prepared country of the Pacific Alliance to confront the economic repercussions of coronavirus. An analysis of the Peruvian Economy Institute (IPE), shows that our finances are more likely to support the economic impact of COVID-19 than Colombia, Chile or Mexico. In fact, this study expresses that our country is the least indebted of the Pacific Alliance, it just represents 26.9% of our GDP. It also has savings over 15% of the GDP and, according to the analysis country risk, its debtor quality remains stable.

The Ministry of Labor and Employment Promotion (MTPE) has implemented a new way of work, which is called remote work for people that work in sectors that develop activities considered non-essential. In this case, we have for example teachers who are working from home. This new way of employment is defined in the Urgency Decree N° 026-2020 (article 16, title II) as the provision of subordinate services with the physical presence of the worker in their home or place of isolation, using any means or mechanism that enables to work outside the workplace. However, it’s necessary that the nature of the work allows them to carry on with their duties from home. Those unable to work from home may apply for a license that permits them to maintain their salary, as long as they redeem the number of hours they were paid once the coronavirus situation comes to an end. A license can be obtained to maintain the employee’s salary without the obligation to compensate these hours. This last measure was implemented by Urgency Decree N° 029-2020.

The electronic devices that employees may use can be both provided by the employer or by the worker (article 19, U.D. N°026-2020). While working remotely, employer and employees need to comply the obligations that are detailed in article 18 of the same Urgent Decree. For example, workers need to be available, during labor hours, to coordinate with their employer.

In addition, the Urgency Decree 038-2020 has been put into motion, which approves the implementation of a perfect suspension of employment with conditions, these measures beneficiate workers and employees of micro, medium, small and medium sized enterprises to fulfil their work contracts and receive an income given by the state of 760 soles (224 USD). They also will have a health service guaranteed by the State. It is also necessary to explain what a perfect suspension of employment is and how it differs from an imperfect suspension. This latter operates when workers don’t work but they maintain the validity of their work contract and keep receiving a salary. This operates, for example, with female workers who cannot work during pregnancy and absent for a lapse of time while maintaining their work contract and their salary. Another case of this are the vacations, in which you, after working hard throughout the year, can go relax on a beautiful beach in Miami and still get paid. According to the article 17.2 of the Urgency Decree N°026-2020, this imperfect suspension of labor also occurs if a worker is infected with coronavirus.

On the other hand, we have the perfect suspension of employment, which is operating in our country due to coronavirus situation. In this case, workers maintain their work contract but don’t receive a salary. Both parts, the worker and the employer, cease, for a lapse of time, to have the responsibility to comply with the obligations that are stipulated in the work contract. This is an exceptional measure and the government is privileging the agreement between workers and employers. In order to mitigate the negative consequences of this practice, workers that are under this statement, can retire part of their fond of Compensation for Length of Service (CTS) (art. 7 U.D. 038-2020).

Chapter III of Supreme Decree N° 003-97-TR is the legal normative that rules when to apply suspension. Article 12 of this Decree explains that it can operate if occurs an event that could be catalogued as force majeure or fortuitous case. In this case, we are stepping into a force majeure event because we can’t control the apparition and expansion of coronavirus and we couldn’t event prevent it, it is outside our dominance. The key point here is that this can last only for 90 days.

While measures have been taken to reduce the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak on workers and employers, another part of society remains in the shadows because of their line of work. Hernando de Soto in his book “The Other Path” (1986) explains that the activity that these workers realize is informal because, in Perú, the cost of emerging to a formal one is too expensive. Actually, they represent 72.5% of our Economically Active Population (EAP) and 18.6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The database of the Minister of Labor and Employment (MTPR) doesn’t proportionate a real number of the independent workers that live on their day to day income because most of them are informal workers and that’s a considerable issue in these times. We don’t know for example the exact number of street vendors that operate through the country. For this reason, when social isolation was first ordered, many of this people decided to disobey the mandatory quarantine justifying themselves by arguing that “if we don´t work, we don't eat”. Informal economy has been a big problem with which Peruvian economy had to deal for a long time and now more than ever.

As we maintain social isolation, there was a crucial debate on the Congress about the Administrators of Pension Funds (AFP). They are, nowadays, in the eye of the storm, and the Congress has decided that workers and employees can retire 25% of the fund that they’ve accumulated during their work years. The amount can’t be less than 4.300 (1.269 USD) and can’t exceed 12.899 soles (3.808 USD).

The International Monetary Fund has said that after coronavirus situation, a global economic recession might be lurking. Considering this, the Minister of Finance and Economy is injecting liquidity in micro, small, medium and big enterprises in order to avoid a stage of massive unemployment. For this reason, the Help Enterprise Fund is giving 300 million of soles (about 88 million USD) to maintain in float small enterprises. Secondly, they have increased the pathway of the program “Crecer”. Although, there are around 80 thousand of fixed term contracts that haven’t been renewed.

National Superintendence of Tax Administration (SUNAT) has implemented a course of action due to coronavirus situation, putting in practice the following Superintendence Resolution: N° 054-2020/SUNAT, Nº 055-2020/SUNAT and Nº 058-2020/SUNAT. This is a new manner to help alleviating enterprises tax burden. Actually, tax earnings have decreased by 17.9%. This is a measure that has been taken globally.

Finally, for those who are poor and the extremely poor, a program has been developed by the Minister of Development and Social Inclusion that is called “Yo me quedo en casa”. Its objective is to provide families in need with 380 soles (112 USD) to help them get through the current situation. However, there is still so much to do considering that, almost 7 million of Peruvians, don’t have access to public services like water or electricity.

In conclusion, as we may have seen, the government is taking a long list of measures in order to mitigate socio-economic impact of coronavirus. Nonetheless, this implicates a great challenge. Fortunately, we have maintained a stable debtor qualification which allows us now to work with the International Monetary Fund. Our National Savings allowed us to react swiftly to this Global Health Emergency. These are the days in which countries all over the world need to ponder over what they value more, which can be human life or economy cost. Decisions need to be taken in accordance with human rights. Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights expresses that we all have the right to the life and it is the government's duty to protect it. Now, during these difficult times, we need to work together, government and society because we both form the State.

I’d like to quote the definition of State of Victor Garcia Toma, Peruvian constitutional lawyer:

“The State is an autonomic political society organized for structuring the convivence, we are a group of people interrelated because of the necessity to survive and perceive common benefit. This requires a relation based on social force and a hierarchical relation between government and society.”

References:

Soto, H. . (2009). El otro sendero: Una respuesta económica a la violencia. Lima: Grupo Editorial Norma.

https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1589/libro.pdf

https://www.ipe.org.pe/portal/el-arsenal-economico-ante-la-crisis-alianza-del-pacifico/

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

García, T. V. O. (2014). Teoría del estado y derecho constitucional .

Political Constitution of Peru (1993)

Edited by Hiba Arrame

The Uncertainties of the Green Deal and Their Effect on the European Economy

Since the first weeks of being President of the European Commission, Ursula Von Der Leyen launched the European Green Deal. As mentioned in the communication of the EC, the European Green Deal aims “to tackle climate and environmental-related challenges; that is this generation’s defining task”. It is part of the EC ambitions to have a neutral economy by 2050. The scale and the scope of this initiative is too ambitions. Regarding the EC, the EU Green Deal seeks comprehensiveness and deepness at the same time and on the all sectors gathering together.

The European Green Deal (source)

Many concerns are raised by interest groups such as private companies, workers and also public institutions about the impact this deal will have on European economies. The first term of transition it is expected to be the Von Der Leyen mandate of 2019-2024, which seated the Green Deal atop its priorities. Any transition phase that has to deal with the economic effects caused by structural changes.

In order to reach the goal of neutral economy by 2050, EC has set-up a mechanism: Just Transition Mechanism (JTM), which will support the EU economies financially throughout the next three decades. It is one of the financial supporter mechanisms along with European Investment Bank. The total amount of financial support established for JTM is estimated to be around 7,5 billion.

The transition phase obviously will have a bill to pay in order to be implemented. The costs are estimated to be around 1 trillion euro, which is a huge amount of money compared to the EU annual budget. The economic sectors directly or indirectly attached to the Green Deal will be charged mostly of energy production and agriculture. Through the JTM, EC is aiming to help the private sector to adjust easily in this transition phase and meanwhile to reduce as much as possible eventual economic costs carried out by the shift of the economic structure.

Where will the money come from? (source)

Implementation of the Green Deal, mainly in the more dependent coal economies, eventually will influence the structure of markets. In the Eastern economies such as Poland or Romania, but also Greece too, coal production of energy goes up to 70% of the total national production. By saying that, the economic challenges for these countries will bring uncertainty to macroeconomic indicators. It is important to keep in mind that last June (2019), countries such as Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary and Estonia refused to sign the commitment to reach carbon neutrality in the next 30 years, because of their dependency on fossil fuels.

Regardless of the challenges its implementation faces, the European Green Deal obviously tends to make possible a sustainable development of European countries. Through the JTM, EC aims to broaden the scope of investment in order to have a flexible economy. In global economy, it is even more difficult to have a clear economic perspective when in the same time countries like USA, China or India are advancing so fast. The EU Commission draft considers this time as an opportunity for “economic growth and prosperity”.

The EU Green Deal eventually is expected to have consequences also on the economic structure of the countries affected. The shift toward a neutral economy unavoidably will impose companies to change the technology production. Probably not all the companies operating in the market will have the chance to be able to continue working. Even though, in the EU Green Deal draft it is mentioned that the initiative will financially support “projects ranging from creation of new workplace through support to companies, job search and re-skilling assistance for jobseekers”, the criteria and the evaluation mechanism of the financing are still unclear.

Identifying the EU Green Deal as a cornerstone of the 2019-2024 Von Der Leyen Commission on the one hand and the important political moment to push political and economic process towards a sustainable development on the other, would be considered as a significant sign for new investment in the economic sector which is highly related to the economic transition. Transport, for instance, is one of the quarters of pollution section in the EU. A shift towards sustainable sources of energy production will affect the European Trading System (ETS) as well. The aim to include in the EU ETS airline and maritime transport has raised concerns by the companies representators about the added costs.

The pressure of the Green Deal is present also in the agriculture sector. Farmers are one of the main parts of the EU budget and it is still unclear if the Green Deal will affect the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP). According to the EU Commission, the plan is to shift the focus from compliance to performance, and in such a case, measures such as eco-schemes should reward farmers for improved environmental and climate performance”. For the farmers the future is even more unclear about the “new technologies” referred in the Green Deal and sustainable foods system, especially after the EU Court of Justice decision to block currently the New Plant Breeding Technique (NPTs).

The financial support of the JTM, must gain also a political consensus on European Parliament (EP), in order to be implemented. Until now, among the EU member states does not seem to exist a broad consensus on the way how the JTM will be financed and how the money will be spent. There exists some political divergence between the members states whom are interested most on the pushing towards the Green Deal agenda and the other who in short terms may be losers from the initiative. There is still an ongoing debate about the budget, where divergences are mainly political, which seems to be the first difficult challenges of Charles Michael to lead towards an agreement and political consensus.

To conclude, the transition phase will be a test for EC if would be able to deal with challenges ahead and in the same time to keep European social cohesion. The shift towards a neutral economy, beyond the advantages in terms of opportunities for growth, circular economy, needs to take carefully into consideration the eventual effects that could be caused especially in the more fragile sectors such as agriculture, which will be affected. Social and economic cohesion should be taken into consideration and especially in such a difficult political time Europe is having actually.

Edited by Hiba Arrame